Alliance Contracting – A Collaborative Project Delivery Model

Originally published in the Spring 2022 edition of the Construction Economist: https://www.kelmanonline.com/httpdocs/files/CIQS/constructioneconomistspring2022/index.html

Introduction

Imagine a large, complex, construction project which does not end with claims and disputes. It sounds oxymoronic. The construction industry is mired in disputes.

The inherent incentives in the typical contract models drive parties to take positions that benefit their organization, typically to the detriment of their contracting partners and generally to the detriment of the project. Those incentives exist at the corporate level but then trickle down to drive the behaviours of the individuals who are managing and building the project. The result is that projects often exceed their budgets, extend beyond their completion date, and result in disputes where no one wins except for the lawyers.

What if there was another way? What if a contract structure could be set-up that promotes true collaboration and best-for-project outcomes? What if, instead of taking positions to protect their organization, project participants were not only free, but incentivized, to find the best solution for the project? What if, instead of suppressing innovation and collaboration, the contracting structure promotes it?

Alliance contracting is the answer. Many of the problems plaguing our industry are solved by alliance contracts and, as a result, alliance contracting has experienced incredible success in Australia, New Zealand, the UK, and beyond. It is now starting to make its way into the Canadian market with the Union Station Enhancement Project and with the Hamilton LRT project.

Alliance contracting shifts the traditional project delivery model on its head. Instead of parties entering a series of bilateral contract (contracts between two parties), they enter into an Alliance Agreement where the owner, contractor (or multiple contractors), designer (or multiple designers), and others all sign a single, multi-party agreement.

An Alliance Agreement is founded on the following key principles: shared risks and rewards, best-for-project decision making, win-win or lose-lose outcomes, challenge and collaboration, unanimous decision-making, equity and transparency, and NO DISPUTES.

The Commercial Structure

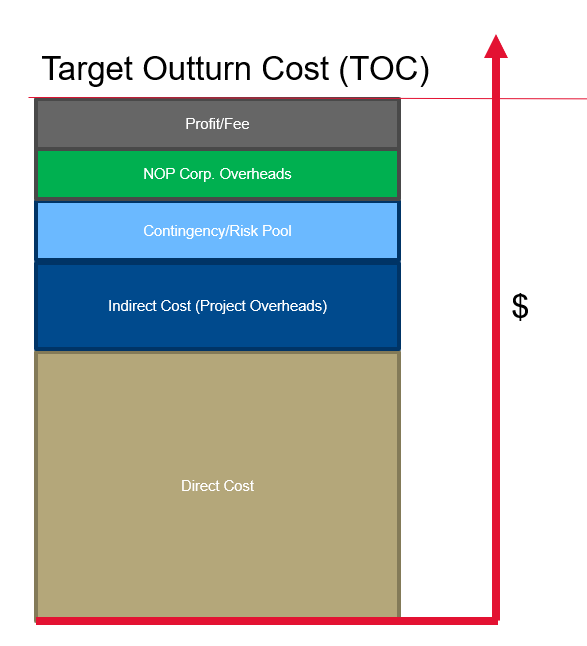

The commercial structure is rather simple and is based upon a “Target Outturn Cost” or “TOC” model with an agreed amount of corporate overhead, an agreed amount of profit, a shared risk pool, and a “Gain Share/Pain Share”.

The Alliance, consisting of both the Non-Owner Participants (“NOPs”) and the owner, collaboratively establishes the TOC. An example of a TOC build-up is shown in the image below.

During performance of the project, the Direct Costs and the Indirect Costs (Project Overheads) are fully reimbursable and are charged and paid on a fully open-book basis. The reimbursable status of the Direct Costs and Indirect Costs is steadfast, even if the actual Direct Costs and Indirect Costs exceed the TOC. In other words, in no event will the NOPs be responsible for payment of any actual Direct Costs and Indirect Costs without reimbursement from the owner.

The risk carried by the NOPs is with respect to their Corporate Overheads and their Profit/Fee. If the Direct Costs and Indirect Costs exceed the budgeted amounts, the Contingency/Risk Pool (if any) may be utilized but then the Corporate Overheads and the Profit/Fee of the NOPs begin to erode. In other words, the NOPs may finish the project with some “Pain Share” – that is a loss of some or all of their anticipated profits and recovery of their Corporate Overheads.

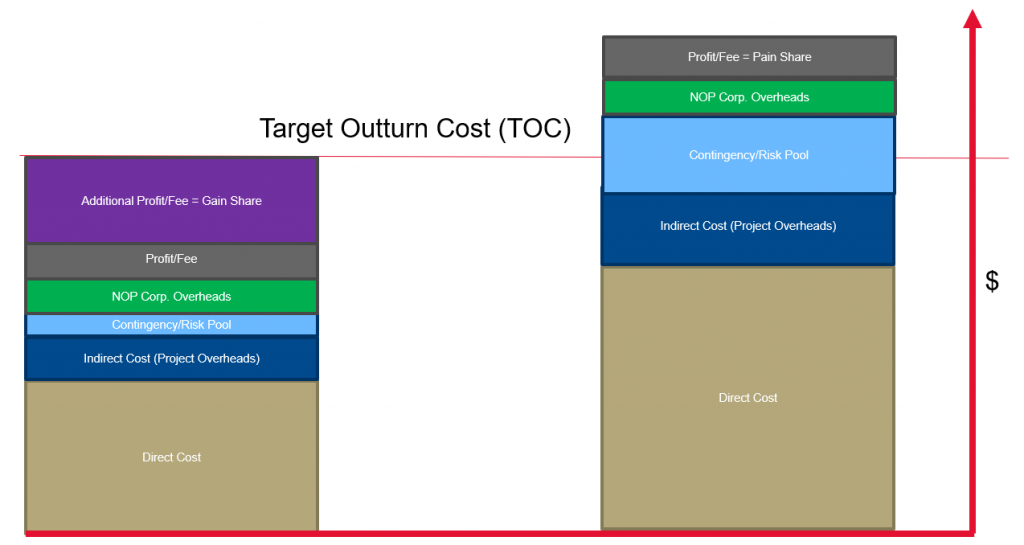

Below is an image of two different alliance project outcomes, one where the actual costs are below the TOC and the other where they are above the TOC. In the first outcome, the NOPs experience a “Gain Share” and their profits therefore increase substantially (the Gain Share may be all or a portion of the savings). In the second outcome, the NOPs experience a “Pain Share” and lose all of their expected Profit/Fee and obtain no recovery for their Corporate Overheads – but still the NOPS are not required to cover the cost overruns.

In addition to the TOC, there may be further incentives available to the Alliance in the form of KPIs which should (although do not always) sit outside of the TOC structure and analysis.

The methods for paying profits vary widely. For example, profits might not be paid until the completion of the project when the actual costs can be compared against the TOC. In other cases, profits are paid out at agreed milestones. Profits may also be paid out as a percentage of profits. In all cases though, the NOPs’ liability is limited to their actual profits (or lack thereof).

The Legal Structure

An “Alliance” is a fictional entity. It is a virtual company. It is a creature of contract.

While an Alliance carries similarities to an unincorporated joint venture, including the critical concept of joint and several liability, the Alliance does not enter into a contract with the owner. Instead, all of the contracting parties and the owner enter onto a single agreement – the Alliance Agreement. The parties to an Alliance Agreement are made up of the owner and the NOPs. This is a major shift from traditional model of a series of bilateral contracts and instead brings everyone, including the owner, into the same sandbox.

The owner and the NOPs establish an Alliance Leadership Team consisting of executives of each party, or project sponsors, much like an executive committee of a joint venture or partnership. However, despite being members of their respective organizations, the members of the Alliance Leadership Team are required, by contract, to act only in the best interests of the project, in accordance with the Alliance Charter. A violation of this requirement is one of the few matters that can expose a party to a dispute and to liability.

The Alliance Charter is an agreed statement of: (a) the Alliance’s vision, (b) the Alliance’s purpose, (c) the principles that the Alliance will adhere to, (d) the objectives of the Alliance, and (e) the expected values and behaviours of all those involved in the Alliance. The Alliance Charter may sound like “fluff”, but it is not. It is a commitment made by the owner and the NOPs and it is a contractual document, binding on all members of the Alliance.

At the level of the Alliance Leadership Team, decisions are to be made unanimously – and on a best-for-project basis in accordance with the Alliance Charter, not by majority rules. This means that the parties are not free to think only about what is best for their organization – rather they must think about what is best for the project. They must challenge each other and work together to find the outcome that everyone can agree is best for the project.

Perhaps most importantly, Alliances have a no blame and no disputes clause in the contract. When entering into an Alliance, the parties explicitly agree not to sue, litigate, or arbitrate with one another (with limited exceptions such as willful default). Importantly, if an Alliance Leadership Team member does not vote in a manner that is “best-for-project” in accordance with the Alliance Charter, it may be a willful default.

Why Does the Alliance Model Work?

The Alliance model is effective as it strips away the barriers to true collaboration by removing the risk that are inherent in other project delivery models. It also aligns the interests of the parties such that what is good for one party is good for all parties. This enables the project participants to share ideas, collaborate, challenge each other, and find innovative solutions to each problem that is best for the project and not necessarily for their individual organization.

When decisions are made on a best-for-project basis, the person or party most capable of performing the job will perform it because that is the best outcome for the Alliance which in turn results in the most cost-effective result. Therefore, if it makes sense for scope to shift from one NOP to another, saving cost, time or both for the Alliance, the scope is shifted.

For an owner, the Alliance model allows not only complete transparency but also ensures that the owner is not paying the private sector to take on risks that cannot be easily quantified (such as system integration risks, legacy utilities, etc.). The owner also does not need to worry about dealing with claims. As recently stated by Kris Jacobson, Metrolinx’s technical project lead for the Hamilton LRT (in an article published in the Daily Commercial News): “That’s the nice part about the collaborative model, especially the Alliance contracting model, we don’t have to waste time debating, you know, what’s an appropriate claim, what’s an appropriate delay.”

But perhaps even more important is that the Alliance gives the owner a seat at the table with the NOPs, not just as their client, but as their partner. In this sense, the Alliance model is the true Public-Private Partnership.

When parties are free to collaborate, be wrong, challenge, and innovate, costs are driven down, schedule is accelerated, and profits are driven up – it is a win-win. But the model does not only drive successful commercial outcomes, it improves the mental health of the participants who are working in a collaborative team environment of mutual success rather than an adversarial environment of win-lose. Not only is improved mental health an important goal in and of itself, but projects are built by people and if the people are happy, they are motivated to work together and succeed together.

An important cautionary note is that the contract alone does not drive success. Rather it is a relationship founded on trust and on mutual challenge, which is then codified into the Alliance Agreement, which drives success. The Alliance Agreement is structured to facilitate this relationship of trust and collaboration, not to create it.

Where Are the Skeletons in the Closet?

Alliance contracting is not soft and fluffy. Like any other contract this is a hard-nosed business approach to construction. Therefore, like any other contract, the devil is in the details. The principles and key features of an Alliance described in this article can be varied and parties seeking to enter an Alliance must be keenly aware of what they are agreeing to. There can always be skeletons in the closet, especially if the owner likes the idea of the Alliance but is not willing to buy into the principle of “best-for-project” and prefers a “best-for-owner” approach. Violations of these principles can come in all shapes and sizes. Of course, an owner will always need to retain some residual discretionary control or power – but the nature and extent of that residual control or power could destroy the very foundation that the Alliance is built upon.

Conclusion

P3 projects flourished in Ontario and in Canada. But their costs have continued to climb as disputes arise and the private sector pushes back on the public sector’s attempts to download all the risk. Hopefully Canadian procurement agencies will soon recognize the benefits of alliance contracting which have been proven elsewhere in the world. The Union Station Enhancement Project is a start. But as the first of its kind in Canada, much is riding on its success and, unfortunately, it deviates from many of the key principles that have driven the success of the pure Alliances that have flourished elsewhere in the world. This risks the viability of alliance contracting in Canada. If the Union Station Enhancement Project is unsuccessful, the Canadian construction market may see it as a cautionary tale and alliancing may be dead in its tracks. Hopefully future Canadian alliances, such as the potential Hamilton LRT, will more closely align with the key principles of pure alliancing. If structured properly, the Canadian taxpayers (and private owners) have much more to gain from alliance contracting going forward.