Breaking Down the Walls: A Series on Construction Delay – Delay Claim Basics

This article was co-authored by Thomas Certo of Ankura

In the fast-paced world of construction, delays can pose significant challenges to project success. In this Breaking Down the Walls series, Gary Brummer, a partner at Margie Strub Construction Law LLP, and Jacob Lokash, an associate at the firm, draw upon their extensive legal expertise to explore the complexities of construction delays. They have collaborated with Thomas Certo, a senior director in the Construction Disputes and Advisory Group at Ankura Consulting Group LLC, whose insights into the technical aspects of delay analysis provide a comprehensive perspective on this critical issue.

Together, they simplify the fundamentals of construction delays, providing readers with the necessary tools to proactively identify and assess delays on their own projects in Canada. At the end of this six-part series, we will have explored the following topics:

1. Delay Claim Basics

2. Delay Damages

3. Disruption vs. Delay

4. Concurrent Delay

5. Forensic Schedule Analysis Techniques

6. Construction Delay Best Practices in Canada

Delay Claims: Understanding the Basics

Construction delay is debated on nearly every construction project in Canada, from the smallest renovations to record-breaking megaprojects. Delay leaves various stakeholders asking seemingly simple questions like: Why was the project late? Who caused it? The answers to these questions, however, can be immensely complex.

In Part 1 of this series, we start with analysing the concept of construction delay and identifying the steps to successfully assert or defend a delay claim. The first step is understanding what delays are.

Exactly what is “Delay”

The term “delay” in the construction context encompasses more than its ordinary grammatical meaning. Merely observing that an activity has taken place later than planned is only the first piece in a complex puzzle to ultimately determining whether there has been a “delay” to the overall project.

The Society of Construction Law’s Delay and Disruption Protocol[1] (“SCL Protocol”) provides a good starting-point in appreciating the meaning of “delay” and the importance of “delay analysis” in the construction context:

In referring to ‘delay’, the Protocol is concerned with time – work activities taking longer than planned. In large part, the focus is on delay to the completion of the works – in other words, critical delay. Hence, ‘delay’ is concerned with an analysis of time. This type of analysis is necessary to support an [extension of time] claim by the Contractor.[2]

Delay analysis is the process of assessing when and why work started later, ended later, or took longer than planned and how these delays affected the overall project schedule. This ultimately allows parties to assert and defend claims for relief, often in the form of an extension of time (“EOT”) claim.

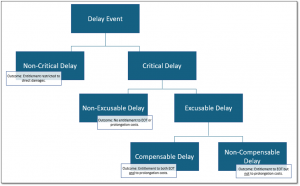

Not all delays are treated equally, and consideration must be given to the contractual entitlement to an analysed delay. There are generally three categories of delay:

1. Critical vs. Non-Critical Delay

2. Excusable vs. Non-Excusable Delay

3. Compensable vs. Non-Compensable Delay

Critical vs. Non-Critical delay

A delay analysis will most frequently employ the Critical Path Method (“CPM”), which endeavours to determine the project’s “critical path.” The critical path is the “longest chain of logically connected activities in a project schedule that, if delayed, will delay the end date of a project.”[3] Critical path delays are discrete (associated with specific events), happen chronologically (occur over time), and accumulate to the overall project delay (discrete delays add up to the total delay).[4]

All projects have a critical path, even if one is not readily identifiable from the schedule. The art of identifying critical activities and piecing together the critical path is aided by an understanding of multiple aspects of the project, including: (i) the ultimate project deliverable; (ii) the contractor plan and schedule; (iii) contractual requirements for sequencing; (iv) the logical relationship between activities; and (v) the physical or logistical constraints of the project; and (iv) how the project events actually occurred (the “as-built” schedule).

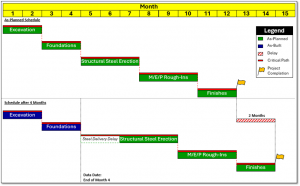

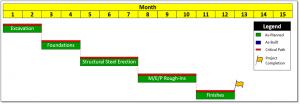

To illustrate a critical path delay, consider the example of a high-rise condominium tower. In order to construct the tower, a logical sequence of work activities is identified in the baseline (“as planned”) schedule. These activities have been simplified and are presented in Figure 1, below.

Figure 1 – Example Critical Path

The planned critical path of our condominium tower begins with site excavation, followed by foundations, structural steel erection, mechanical/electrical/plumbing (“M/E/P”) rough-ins, and finishes. The completion of finishes marks Project Completion. The construction of this condominium tower is planned to take 12 months in total.

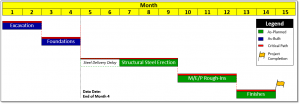

We now move four months forward into the construction period, with the status being shown in Figure 2, below.

Figure 2 – Example Critical Path Four Months into Construction

Both the excavation and foundation activities have been completed during these first four months, consistent with the planned critical path. However, the construction team has now learned that structural steel deliveries are delayed by two months, meaning that the structural steel installation is also delayed by two months and cannot be installed according to the original plan. Because structural steel erection is on the critical path, this two-month delay to the start of structural steel erection will also result in a two-month delay to Project Completion if structural steel erection and all other activities are completed according to the go-forward plan.

A comparison of the two schedules (the as-planned schedule versus the schedule after four months) shows how the critical steel delivery delay is projected to impact Project Completion, shown in Figure 3, below.

Figure 3 – Example Project Completion Delay from Late Steel Deliveries

Conversely, a non-critical delay would be a delay to an activity that does not impact the completion of the project. These activities can be delayed on their own without impacting the critical path and can be said to have “float”. Using the M/E/P rough-ins from Figure 3 above as an example, any discrete activity delay which does not impact the contractor’s ability to install the M/E/P rough-ins at the beginning of Month 8 is not critical. For example, if the design were received later than planned, but still prior to the start of Month 8, that design delay is not critical because the start of M/E/P rough-ins is controlled by the completion of structural steel erection at the end of Month 7.

For purposes of developing the critical path, non-critical delays are set aside because they do not delay completion of the project. That is not to say that non-critical delays may not result in a claim – they could; however, the claim would be for the discrete impacts caused by the non-critical delay and not, for example, overall prolongation.

Identifying critical versus non-critical delays is a key component of schedule delay analysis, and often one of the most contested facts during a construction dispute. The fundamentals of schedule analysis and critical path delay identification will be discussed further in Part 5 of this Breaking Down the Walls series, “Forensic Schedule Analysis Techniques”.

Excusable vs. Non-Excusable Delay

Once the critical delays are identified, the next stage of analysis involves determining whether the critical delay events are either excusable or non-excusable. This is a legal analysis which examines both the terms of the contract and the applicable jurisdictional legal principles to determine a party’s entitlement to claim relief for the delay.

Often, excusable delays are delays caused by an unforeseeable event beyond the control of the contractor or subcontractor, also referred to as an “Employer Delay”.[5]

Classifying a delay as excusable depends on several factors, most importantly the allocation of risk under the contract; however, generally, the following are considered excusable delay events:

1. Acts of God (also known as force majeure events), which include various natural disasters, fires, or floods;

2. Labour strikes or changes in law, which force the contractor to suspend or delay works;

3. Delays caused by the owner or its agent, including but not limited to design changes, failure to provide undisturbed access, or errors and omissions in plans or specification provided by the owner;

4. Differing or concealed site conditions, such as unknown utilities; or

5. Lack of action or interference by outside agencies, such as permit approvals.

When a delay is excusable, a contractor is entitled to an EOT, also referred to as an “Employer Risk Event”.[6]

Thus, a contractor cannot be held in default for a delay that is deemed to be “excusable”. However, an EOT does not necessarily mean that a contractor has an entitlement to additional compensation (this differentiation is addressed in the next section).